Issue #97

Guten Morgen!

Welcome to another edition of the Krautshell! This week, Jonny takes a deep dive into a significant reform to Germany’s social welfare net and puts it in some historical context. In addition, our main articles examine a major court ruling and its ramifications for the Commission’s struggle with Big Tech, Germany’s (increasingly isolated) Covid preoccupation, and the German weapons deliveries to Ukraine. Finally, enjoy Anna’s use of bovine metaphors to describe the unenviable situation of Germany’s economics minister, Robert Habeck.

As always, have a great weekend!

Anna Christian

FIRST, SOME SOLID INTEL:

European Commission: 1:0 Google

As the European Commission (EC) is on a war path to reign in the power of Big Tech with its double whammy of Digital Markets– and Services Acts (DMA and DSA, respectively), European Commissioner for Competition Margarethe Vestager recorded a major victory this week. On Wednesday, the European Court of Justice delivered its decision to uphold a fine imposed on Google for uncompetitive practices linked to its Android mobile operating system. Here’s what you need to know and what this means for the future of competition policy in the EU.

As we mainly want to focus on the impact this decision has going forward, here’s the summary of events in a [Kraut]shell. Back in 2018, the EC fined Google 4.34 billion euros for deals the California-based company struck with smartphone manufacturers to make Google the default search engine on their devices. This decision is indeed monumental in the world of tech, as there’s an expectation that it’s the first of many cases that will be decided within the scope of the DMA and DSA era of regulation. The DMA is set to kick in in mid-2023, and this decision is likely to strengthen Vestager’s (and whoever her successor will be in 2024) resolve to critically analyze other business practices from the big tech sector it finds unkosher. Big tech’s response: lawyering up. Recently, an EC representative who works in big tech regulation stated that meetings with big tech companies are getting fuller and fuller, as there are easily “15, 20, 25 lawyers around the table.” What this means: gloves are off and it’s time to look for loopholes. What’s coming next on Vestager’s long march of antitrust? (we imagine it a little something like this…) If you ask us: anything related to user data storage and -use, digital payments, and online marketplaces & app stores. We’ll be sure to keep you updated.

Covid: Germany’s Sonderweg Continues

The tenacity of German policymakers is a remarkable thing. For many years before the Ukraine war, friends and allies warned our leaders that new pipelines and energy dependency on Russia might not be the brightest idea – they went ahead anyway. Similarly, the government is intent on quitting nuclear by the end of the year no matter what Germany’s energy requirements or the vast majority of the population have to say. But here’s the strangest one of all: Health Minister Karl Lauterbach visited Israel this week to praise Germany’s Covid policies as “the strictest in Europe”, somehow overlooking the fact that for most of the world, Covid is no longer treated as a major policy concern. Not only that: Germany’s Sonderweg (Special Path) is increasingly becoming a national embarrassment.

A case in point is Germany’s new Infection Protection Act, which even the greatest health policy wiz will struggle to understand. Apart from confusing testing requirements, individual states can mandate masks in restaurants and bars – except for the recovered, tested or freshly vaccinated – but not in shops and supermarkets (which are apparently Covid-proof). Meanwhile, FFP-2 masks are mandatory on public transport and trains across the country, while masking on flights was recently dropped after a scandal involving unmasked ministers and journalists on an air force jet to Canada (here’s the drama). It’s all a bit of a muddle, especially considering that neighboring countries have dropped their Covid restrictions and people rightly assume that Germany – in the throes of a historic energy crisis – has more immediate issues to deal with. One might hope at least that our leaders combine their confusing policies with a sense of irony and self-awareness, but far from it. When a far-right parliamentarian called him “nuts” during a recent Bundestag debate, Lauterbach, rather than respond with reasonable arguments, proudly announced (on Twitter) that he would sue her for libel. If nothing else, this demonstrates to what extent Covid has harmed civilized debate in Germany.

Germany’s Arms Deliveries to Ukraine

Since before the invasion of Ukraine in February, a common criticism levelled against Germany has been that it is insufficiently supporting Ukraine with military equipment. For example, Germany’s shipment of 5000 helmets was criticized by Ukrainian leaders as a “purely symbolic gesture” and a “drop in the bucket”. More recently, the German government has come under fire for allegedly dragging its feet on delivering further heavy weaponry, particularly Leopard 2 tanks, in order to support the counteroffensive in Eastern Ukraine.

What these criticisms and calls for further military support often blend out is that Germany has made and continues making substantial military contributions to the Ukrainian army. These contributions range from thousands of anti-tank weapons to 3 cutting edge multiple rocket launchers “Mars” with ammunition (a complete list is regularly updated by the German government).

Military analysts recently pointed out that the volume of arms delivered by Germany exceeds that of every other country besides the USA and the UK. Not only have large amounts of arms been delivered, but they have also shown themselves to be critical in the ongoing counteroffensive that has liberated larger swaths of Eastern Ukraine. For example, Ukrainian military intelligence sources have highlighted Germany’s Gepard, a set of anti-aircraft guns on tracks, as crucial equipment to combat Russian aircrafts during the offensive. As a result, Russia was reluctant to utilize its fighter jets to stop the Ukrainian advance and the Russian air force appears to have suffered losses when they did engage Ukrainian forces.

Therefore, the commonly held perception that Germany is making woefully inadequate contributions to Ukraine’s defense effort is misleading. Overly bureaucratic processes and domestic political realities did stall Germany’s support, but over the past 7 months it has stepped up and made contributions that are meaningfully aiding the ongoing Ukrainian counteroffensive.

TAKE A BREAK, GIVE YOUR EYES A REST.

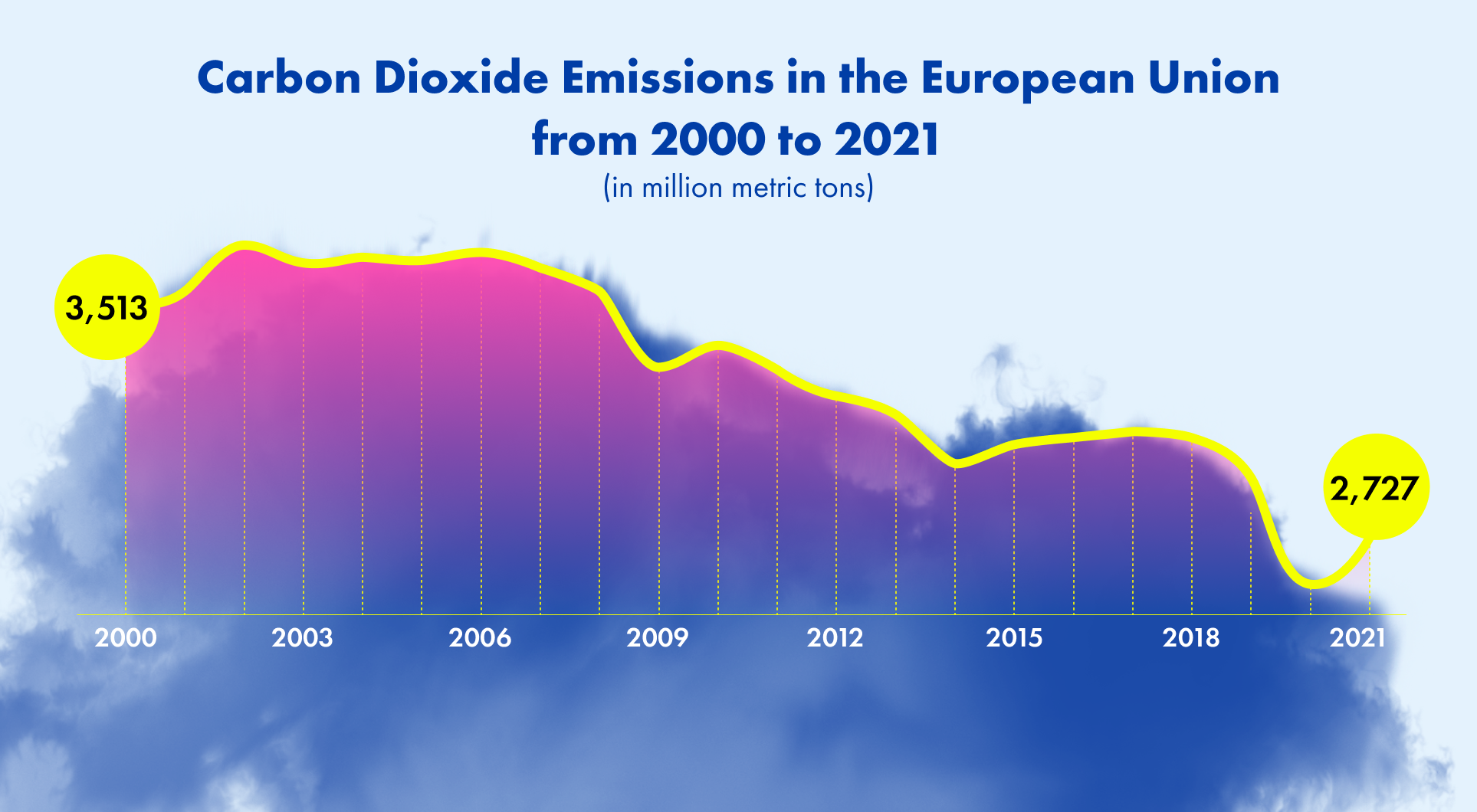

Source: Statista

THE HOUSE’S VIEW:

by Jonny

Bürgergeld – The Nerd Edition

It’s about time we talk about a nerdy topic. This week, after a long run-up, the most important social policy project of the traffic light coalition found its way through the cabinet. That means a compromise between the three governing parties was negotiated. It is about an update in the German social system, specifically about the benefits that the unemployed should receive from the state in the future. What the so-called “Bürgergeld” (transl. “citizens’ income”) is, how it differs from its predecessor and how it came about in the first place is what we want to shed light on today. Sit back for a journey through German domestic politics. With the knowledge you’ll gain here today, you’re sure to be the coolest person in the room at the next party!

“The Sick Man of Europe”

That was the less than charming name for Germany in the EU in the early 2000s. Germany had high unemployment, demographic change was looming and in general the German labor market was not doing too well. It was Gerhard Schröder, of all people, chancellor and SPD chairman, once a “socialist” by his own account, who had to introduce a neoliberal labor market agenda. A key point of this “Agenda 2010” was the reorganization of basic welfare benefits, which in Germany go by the infamous name of “Hartz IV.”

Hartz IV, or officially “Unemployment Benefits II,” is designed to enable people on basic benefits to live a life that is just about commensurate with human dignity. It promises a basic income of currently 449€ for a single adult per month. The additional costs for housing and heating are also covered (with certain difficult exceptions that we ourselves hardly understand).

The Criticism of Hartz IV

Let’s be honest: whoever has to live on Hartz IV is not doing well. It is perhaps just possible to survive, not more. However, and this must be clearly stated, this is the way it was conceived. It arises from the neoliberal logic that whoever has to subsist in (almost) inhumane living conditions quickly looks for a job. To ensure this, the Hartz IV system also has sanctions. Receiving benefits is also accompanied by obligations: regular appearances at the job center, acceptance of mediated jobs, no matter how little they fit with one’s own education. Non-compliance? Reduction of the 449€ by up to 30%.

The fact that the SPD of all parties, the supposed advocate of the workers, the friend of the “little man”, had to introduce Hartz IV is not without a certain irony of fate. If you look at it globally, Agenda 2010 and all its measures have probably turned Germany from the sick man of Europe back into the strongest economy in the EU. This is one of the few successes that can still be attributed to Gerhard Schröder – and an action that for once has pleasantly little to do with Putin. Nevertheless, the SPD was punished by its core electorate. Voters from the CDU and FDP applauded, but they still preferred to vote for their own parties.

Correcting the Historic Mistake?

The sanctions in particular, but also the low standard contributions, have been met with much criticism. There are also studies that show that the sanctions are completely ineffective. That’s why the new Bürgergeld is the SPD’s heartfelt project; it’s supposed to represent a reconciliation with the old, disappointed voters who have migrated to other parties or don’t vote at all anymore. Chancellor Scholz, who was the SPD’s secretary general at the time Agenda 2010 was drafted and is often referred to as its “architect”, is now set to go down in history as the creator of the Bürgergeld.

The Bürgergeld increases the standard contribution rates by 53€ from 1 January, it reduces the sanction level and suspends the possibility of being sanctioned at all during the first half year of receiving benefits. Furthermore, it increases asset protection – until now, you had to have demonstrably spent almost all of the private assets you had saved up as retirement provisions, for example, before you could receive basic benefits. Lastly, the new citizen’s income significantly promotes the education and training to qualify for better jobs.

An Improvement or Not? The House’s View

In macroeconomic terms, the Agenda 2010 must be considered a success. However, it did not only consist of Hartz IV, but also introduced many structural improvements in job centers, for example. A life on Hartz IV is hardly compatible with human dignity. And many people are not unemployed by choice. Personally, what bothers me the most is the idea, based purely on the homo oeconomicus worldview, that more pressure on the basic pillars of one’s existence will increase the will to work. Many studies today show us that this is not so. That rather a certain “security” – and by that I just mean knowing that you can afford dinner that night – is much more likely to make people want to get a job.

The citizen’s income is not intended to be an unconditional basic income, which is why there is still the possibility of sanctions. FDP leader and Vice-Chancellor Lindner recently said the telling sentence: “Solidarity is not a one-way street.” So, pity has to be earned, and those who are already living at subsistence level and on the borderline of inhumane conditions should still dutifully say “thank you,” and of course not be too much of a burden on society. It is a selective understanding of liberalism that the neoliberal political forces in Germany currently have. The FDP has bowed to the plans; after all, it sits in the government. The CDU and the employers’ associations are filled with anger. Let them.

LONG STORY SHORT:

- State of the Union: This week, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen delivered her “State of the European Union” address, giving a status quo of current priorities in the EU. Unsurprisingly, the war in Ukraine, energy security, and supply chains featured heavily in the speech. If you want to watch the whole thing, take a look here, and bring your Bingo card!

- Government Takeovers on the Horizon: Ever since Russia stopped the flow of gas through the Nord Stream pipeline this summer, the financial situation of German energy companies has further deteriorated. The government has now announced that it is considering further bailouts of energy providers, including a potential takeover of Germany’s largest gas company, Uniper, along with VNG and SEFE.

- Got Any Spare Change? The German government’s budget for the coming year has been decided upon, and it’s a mixed bag. After all the hullabaloo about Germany becoming more digitized, the Ministry for Digital Affairs saw a significant budget cut, and the Ministry of Health had to take the biggest losses with their budget cut by almost two-thirds.

WHAT’S ON OUR MINDS:

HOLY COW

One person has been standing out in the news cycle in the last months: Robert Habeck, our Minister of Economy and Climate. It’s probably fair to say that currently he has the hardest job in the country, trying to figure out Germany’s energy and gas supply during the upcoming winter months, without putting too much hardship on the citizens.

But the Russian gas delivery curbing, the financial well-being of the citizens, the economic endurance of the industry and his own deficient understanding of economic concepts are not the only restrictive variables he has to factor in: The green ideology adds another layer of challenge, and this one makes some decisions harder, if not impossible, to reach.

Looking for solutions in the Middle East he has to turn a blind eye to the human rights issues, subsidizing fossil fuels he has to forgo the climate aspirations, looking at a prolongation of operating nuclear plants, he has to slaughter the holy cow: a fundamental refusal of nuclear energy, basically the foundation the Greens party was built upon in the 80s.

Watching Habeck’s teeny-tiny steps from “Nuclear energy does not solve our problems” to “Maybe we should keep our remaining nuclear plants as a reserve” to what, I am sure, will become “We need the nuclear plants” is almost painful. But I kind of empathize. The vast majority of the German population supports the prolonged use of nuclear energy. Only 12% of Green voters do. Once he gets to the inevitable, he might very well become the cow his party will slaughter.